The film The Matrix haunts me on SO many levels, but this ramble is not about science fiction or film or conspiracy. It’s about family (Surprise!), and maxims’ role in the larger code of family programming. A maxim is a brief statement of a general truth, principle, or rule for behavior, according to the Cambridge English Dictionary. This shall be the first in a series about my family’s favored maxims and the ways those have woven into my identity.

I’ve been sick for 12 days and eating intermittently when I don’t feel nauseous. Just now, I was hungry. There’s not much in the fridge or pantry that wouldn’t take energy to prepare or doesn’t threaten to upset my gut, so I grabbed a packet of crackers and began to munch. “Blech! Why don’t I toss these?” I wondered. I’d purchased them for $1 at Ocean State Job Lot a few months ago and regretted it.

As soon as the liberating thought occurred, as it had every time I ate one of the cursed things, the familiar voice asserted itself:

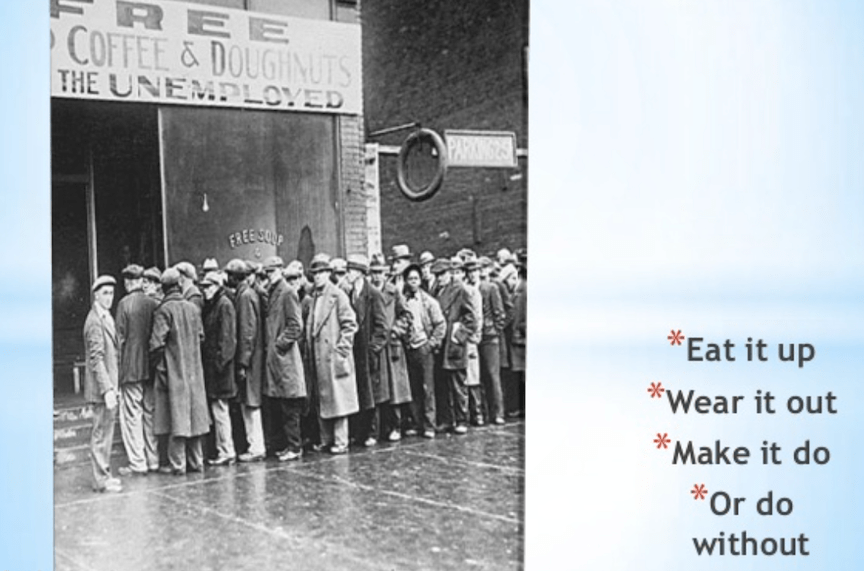

Eat it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without.

In my head, it’s an anonymous voice, but in my life it boomed in my grandparents’ voices, my great-aunties’, my uncle’s, and my mother’s. It meant that it’s irrelevant if you like or do not like something. It’s irrelevant if an article of clothing is uncomfortable, has a small stain or tear, or does not fit. It’s irrelevant if an item doesn’t work quite right, or you lack what you need to get something done. You make do with what you have (and you’d better be grateful for that), or you do without. Period. We do not want to hear about it.

As with so many of the maxims we grow up absorbing, they contain important lessons for living a balanced life. I suppose this is why they have become maxims. Repeated often in the context of a dysfunctional family to a young child, however, maxims’ truths or life lessons can become twisted and serve instead as forms of mind control whose effects are long-lasting.

Imagine for a moment a seven-year-old sitting at the dinner table with their parents. The meal happens to be a favorite one. In a pause amidst a verbally assaultive argument, Father passes out, his face mashed in the spaghetti. Child freezes. Mother turns to child chatting about the day in a now seemingly normal voice, including unconscious Father in the conversation. And insisting that child do the same. When child fails to respond or eat, Mother’s voice and eyes take on the familiar sharp edges. She taps child’s plate with her fork in rhythm to the harsh words, “Eat. It. Up.” She doesn’t need to say more. This family operating system is running. The remaining words of the maxim need not be voiced; the shortcut is enough. The full app, including the add-on of reality denial and normalcy pretension, initiates. If you are able to imagine this scenario and the child’s experience of the maxim within the overall family program, then you will understand, perhaps, the long-lasting effects that even a handful of words can have. Some people might call them a trigger.

In terms of my particular cracker situation, none of this is a big deal. A little obsessive maybe. Same with so many other things. I remember being shocked when a friend told me she replaces her white shirts, socks, and underwear annually because they get dingy. Seriously? I thought. You do that? I suffered a moment of confused moral outrage and envy. Occasionally I throw things away and wish I could enjoy the release of the long abjured sacrament of Reconciliation (aka “confession,” a sacred routine in the Catholic Church in which one tells one’s sins to a priest with heartfelt regret, is absolved, does penance, and is reconciled with God). I never felt that release of Reconciliation, even as a child. Somehow this inability just added to the long list of things wrong with me. I long to discard things–and beliefs–without guilt.

I am a master of repairing, recycling, and repurposing. For example, I’ve recently rewired six old lamps (some of which I don’t even like); I use discarded wooden wine crates as plant stands; and I’m quite enjoying my clever idea to turn unused, tarnished Revere bowls upside down to create shiny pedestals for my laughing buddha and other statuary. All that said, I also giddily enjoy buying new things despite the inevitable guilt chaser. Everyone tells me the guilt is because I grew up Roman Catholic. Saying “It’s ‘Catholic Guilt'” is akin to describing the Bayeux Tapestry as a picture of a bunch of guys and horses and stuff.

No, the guilt results from programming within a complex Family-Church-School matrix. Their threads were as tightly woven and knotted as any tapestry or embroidery. Some of the programming was purposeful; most of that I won’t address here. I choose to believe that some of it was unintentional, such as the maxims.

As all children are, I was a receptacle into which the adults around me poured their understandings of the world, how to live in it, what I should think, and how I should behave. A lot of it was decent stuff. Some of it was sick. Most of it stuck. Unfortunately, some of the sick stuff stuck subtly; it didn’t dawn on me until late in life how ingrained that early programming had become and how much it affected how I understand who I am and how I think and behave.

I’ve long wanted to write about my family’s favored maxims and explore why these pithy bits of wisdom continue to carry such an emotional charge for me. Until now, I had not thought to use the internet to track down the origins of their favored scripts. It turns out the maxim I quoted above is attributed to New Englander Calvin Coolidge during the food, clothing, and other shortages that began just after the United States entered WWI in 1917. It gained renewed popularity during WWII rationing with the replacement of “eat it up” with “use it up.”

That my grandparents would have embraced this maxim makes sense as it does that my mother and uncle, their children, would have. My grandfather was raised in poverty, one of 8 or 9 surviving children of Irish immigrants to Boston, and a WWI veteran. His wife, also a child of Irish immigrants, struggled after her father died leaving her mother to care for 8 or 9 young children alone. My grandparents raised their children during the Great Depression. My father also grew up during the Great Depression and was a WWII veteran. His father died in 1939, leaving his wife and three children to struggle in desperate enough poverty that my father told stories of leaving apartments in the night because they could not pay the rent, and of searching for food. All the members of my family were adults during WWII.

So, I grew up with people who had personal familiarity with the wisdom of “Eat it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without.” No matter that all of them, with the exception of my grandmother, had professional careers. We were not wealthy, but we did not lack financial security. Our pasts stay with us, though, in one way or another.

My father, like some who find their way out of poverty, liked to spend money (especially on himself) and occasionally scoffed at the maxim, but my mother’s side of the family took it as seriously as they did Church law. It was a HUGE deal to fail to eat one’s food, to purchase anything not deemed absolutely necessary, or to have to discard something broken beyond repair. There was much gnashing of teeth and tearing of hair–almost literally, and infractions were neither easily forgiven nor quickly forgotten. Who knows? One of the sayings in my family was, “Well you know, we Irish have long memories.” Maybe that’s what it was. Let’s just say that the culture of my family made the following far more fraught than than they ought to have been: heat; electricity; food; clothing; books, paper, toys, art supplies; personal care products; Christmas; and the usual accidents that occur when household items and an active, imaginative child occupy the same space.

I can choose to throw away the disgusting crackers, toss my turtlenecks, and take the box of potentially useful stuff to my local transfer station’s “Treasure Chest.” What I can’t seem to do is overwrite the faulty programming in my operating system. Certainly, the maxim, “Eat it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without” was intended to teach frugality. This seemingly lost virtue is why the maxim has been repopularized; it is all over the internet on sites about living life more simply in our culture of overdoing everything.

Instead of learning frugality, I learned that I was a bad person, generally. And, according to family maxim-law, I was. I fed my food to the dog under the table or barring that, went to the bathroom to spit it out. I cried and complained because my shoes pinched and my clothes itched. In a desperate effort to find relief and justify replacements, I’d sometimes fling myself off the tire swing to shred the clothing that tortured me (and my skin along with it), or drag my too-small shoes on the pavement while I rode my bike in an effort to wear them out. I was whiny about being cold because the heat didn’t reach my bedroom. I read books too quickly, used too much paper for writing, wore out crayons too fast with drawing and coloring, and grumbled constantly about wanting more. I received Christmas gifts (mostly not wished-for items) for which I was accused of being spoiled. And I spilled and mangled and broke things (not on purpose). I reaped punishments and censure for all these failings.

Worse than any of those consequences was the glitch that happened in my program. I developed a fear born out of a misunderstanding of the last part of the maxim. The “or do without” in the maxim simply means, you make do with what you have, or you don’t. Eat the disgusting crackers or don’t. Easy-peasy.

A child’s mind is, however, more labyrinthine than many adults imagine. In my mind, the words culminate in the utterly irrational conclusion that if I don’t finish the crackers, then I am a bad person; and if I am a bad person, then I will reap consequences. Specifically, things I care about will be taken away from me. In this cracker-scenario, I experience an absurd dread that if I throw the crackers away, I will at some undefined point in time find myself in a world where there is no food available to me, and I will starve to death while suffering the effects my hubris. I will discover, to my great horror, they were right that I am a bad person and I ought to have honored the wise rule of my elders.

How did this happen to me? It resulted from a triad of logical fallacies that grew from my lived experience. It wasn’t about crackers or crayons. It was about everything. First, I grew up in a deeply superstitious home where people believed that the universe or God or something would rain down blessings or misfortune upon you depending upon a whole set of strange behaviors that must be followed, the family maxims among them. And I wasn’t wholly successful at following the maxims or any of the rules. Ergo, I invited misfortune to rain down upon me and deserved what I got. This maps onto another family favorite maxim: “You made the bed; now sleep in it.”

Second, I grew up in a conservative Roman Catholic home where people believed God was always watching. Similar to Santa Claus, I thought; I had the two confused for quite a long time and once made the disastrous mistake of asking for clarification. Consequences were just as likely to be meted out in this life as they would be in the next. Another favorite family maxim was, “God helps those who help themselves.” The inverse seemed to me that God punishes those who don’t help themselves–in this case, me because I was not following the Family/Church/School rules. My family weren’t big bible-quoters, but I spent seven hours a day with teachers who were, and who used the bible, selectively, for crowd control.

Maybe because I grew up during the Cold War and was exposed by my ultra-conservative, news-junkie parents to constant talk of geopolitics and daily images of body bags, Vietnam atrocities, and various world disasters, it was never clear to me that the end of the world was not an impending reality. God might show up at any moment to wreak his undefined but obviously horrific vengeance on us. My teachers’ words were even more terrifying to me than the other forms of abuse they employed. Among a choice few I recall are:

For it is because of these things that the wrath of God will come upon the sons of disobedience… (Colossians 3:6)

For behold, the Lord is about to come out from His place to punish the inhabitants of the earth for their iniquity… (Isaiah 26:21)

I will warn you whom to fear: fear the One who, after He has killed, has authority to cast into hell; yes, I tell you, fear Him! (Luke 12:5)

My third grade teacher favored this non-biblical gem. Somehow I knew enough about Siberian prison camps and scary Soviets to be utterly cowed by her threat. In 1972-73, Sister Marie V. would frequently turn red under her wimple, shake her fists at one or all of us, and shout:

If you don’t ___, I’ll send you to Siberia where the Russkies’ll know what to do with you! This was sometimes shortened to: To the Russians!

Thirdly, I grew up in a home where things I cared deeply about actually were taken from me. I don’t refer to the taking away of my dignity by spankings or other public embarrassments, or the invalidation of my feelings via other routes. Actual things were taken from me regularly at random times and for no apparent reason. One night, for example, my father took my valued collection of coloring books and used them as kindling for the fire. Another time, he threw my precious security blanket out the window into a snowstorm. And one day I came home from school to find that my mother had put all my beloved stuffed animals out with the trash. In a tangled, knotty way, this only served to confirm the truth that I ought to be able to “do without.” The only way I could make sense of these inexplicable acts was to conclude that they were some sort of karmic payback for being a bad person and that I needed to try ever-harder to be good.

That, being “good,” was a slippery golden ring to grasp and shall be the focus of the next piece in this series.

If you haven’t already, you might now ask, “What’s your point?”

Hmmm. Be careful what you say to your kids? Ask yourself about why you do some of the eccentric things you do, or why you think in certain odd inner-conversational loops? (Admit it; we all do.) What’s my point? It’s a good question, but I don’t have a point per se. I write about various personal experiences for two reasons. Obviously, it helps me wrangle chaos, but if it were only that, I wouldn’t put it on a blog. Somewhere in me glows the small hope that something I write will resonate with someone who reads it and spark their own healing. I’ve been lucky to have had that happen to me, and would like to pass on the blessing.

This was riveting to read, as your blog writing always is. I felt both moved by and outraged over what you endured as a child, in this particular recollection repeated brain-washing maxims, quoting the Bible for crowd control via fear-induction, and assorted acts of random cruelty committed by your parents and certain teachers. You survived all this and are healing into Self.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am pleased to hear the word “riveting” tied to my writing. I credit Mr. Rogers for getting me through my childhood. Songs like this saved me https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1654116367978446

LikeLike

Holy, wow! This shook me to the core. The way you’re able to evoke such emotion while also making me burst with laughter is amazing. I love you! You are valid! I see you! ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person